With the arrival of spring, respiratory illness season is beginning to decline. As the sound of coughing and sneezing recedes across the country, several pictures are emerging from data collected this winter.

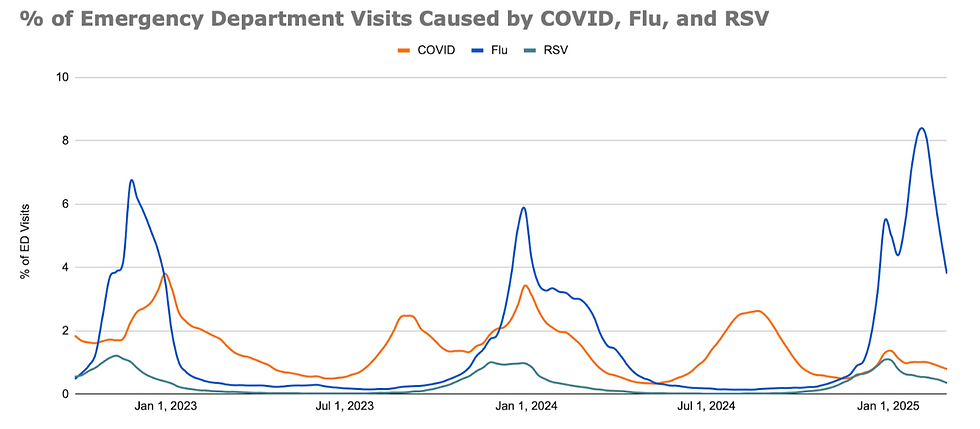

For one, there has been a surprising shift in viral dominance among the three big respiratory viruses. COVID-19, the infamous driver of respiratory hospitalizations in recent years, was unusually mild. While thousands are still dying from the virus each month, this winter saw the smallest COVID wave in terms of severe illness since the pandemic began in 2020. RSV, a cold virus that primarily hospitalized children, circulated at normal levels.

However, the overall respiratory season was far from mild—in fact, data indicates it was quite severe, and readers likely experienced that in their own communities. The culprit? An extraordinary resurgence of the influenza virus (the flu). For the first time since 2020, the flu has been causing far more severe illnesses than COVID and RSV combined.

Overall Illness

Data from emergency departments across the country, a good marker for moderate illness, shows extremely high levels of Influenza. Currently, the flu is causing about four times more emergency department visits than COVID-19, which is already twice as prevalent as RSV. It’s a big change from past years when flu was somewhat less common and COVID was far more prevalent. Only RSV has stayed mostly consistent. Fortunately, all three viruses are now declining as spring arrives and immunity builds up from the huge number of infections in recent months.

Data for other diseases is harder to come by. However, emergency department visits for Acute Respiratory Illness (ARI), which includes the three respiratory viruses and other illnesses like bacterial pneumonia and colds, are also down. Activity is still high across much of the country, however, and may take weeks or months to return to baseline.

Possible Explanations

There are many likely reasons for the most dramatic change this winter—the lower rate of COVID-19. Some of these are complex factors that we cannot explain for sure, but a few major reasons have emerged. Firstly, in recent months, the constant churn of new COVID variants, which escape our immunity and enable the virus to drive new outbreaks, has slowed. The virus is still evolving, but without the emergence of a major new variant since the appearance of the JN.1 variant last winter, COVID simply had less fuel to run on this winter. This also means that vaccines, which are being given out at higher rates this winter compared to the past, are better matched—and while data is lacking so far, vaccines should have at least somewhat more effect this year.

It helped that there was a substantial COVID wave this summer, leaving less vulnerable people to infect in the winter. There has also been an overall trend of less COVID activity since the start of the pandemic when no one had immunity to the virus.

The other virus displaying unusual activity is the flu, which comes with its own explanations. For one, this flu season is dominated by flu A, which is generally more severe than the other major flu virus, flu B. Additionally, both subtypes of flu A—H1N1 and H3N2—are out in force. Infections with one don’t necessarily provide strong immunity against the other. H1N1 generally hits young people harder, while H3N2 is deadlier overall due to its severity in the elderly, making people across all age groups more vulnerable. On top of that, the flu shot is poorly matched this year, meaning the flu A strains included in the vaccine don’t provide as much immunity against the actual flu A strains circulating.

Other factors could include the disruptive effect the pandemic had on the behavior of all three major respiratory viruses, the competitive effect each virus has on the others, and vaccine uptake. There are likely many other factors contributing to the flu upswing, but it will take time to elucidate all the causes.

Severe Illness

Consistent with emergency department visits, COVID-19 hospitalizations were extremely low this year compared to previous winters, barely exceeding the number caused by RSV. This year’s peak, which occurred in the first week of January, saw admissions level out at just half of last winter’s peak, which was, in turn, lower than the previous winter’s peak. It’s a long way from the dark days at the height of the pandemic when peak hospitalizations were about eight times higher than they were this January.

Since the collection of hospitalization data for RSV didn’t begin in earnest until this fall, it’s more difficult to compare RSV seasons than with the other big respiratory viruses. However, data from RSV-NET, a smaller surveillance network, indicates a similar, if not lower, number of hospitalizations compared to past years.

Influenza, on the other hand, surged to record highs this winter. At its peak, this flu season was hospitalizing more Americans than any COVID wave since the arrival of the Omicron variant. This is by far the worst flu season since the pandemic disrupted flu patterns in 2020. Comparisons with pre-COVID seasons are harder since data collection was more spotty then. However, a preliminary assessments from the CDC indicates that this year’s flu season is on par with, if not worse than any flu-season in recent history in terms of hospital burden.

Since the reporting of deaths varies quite considerably between viruses due to different types of testing, it’s more difficult to determine the exact impact on mortality of these infections. Thankfully, we aren’t seeing huge amounts of excess mortality (deaths above normal) like we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic or even at the peak of the 2017-18 flu season, the deadliest flu season in recent history. This isn’t to say that the huge numbers of hospitalizations aren’t translating into many deaths, however. To date, the CDC estimates that since last October, at least 23,000 Americans died from COVID. At least 8,300 more died from RSV, and 22,000 died from the flu. This is just the lower estimate; the upper estimate indicates the true death rate could be several times higher.

With flu hospitalizing people at levels not seen since before COVID and COVID itself placing an extra burden on hospitals that didn’t exist before 2020, the situation isn’t exactly bright for hospitals. Throughout this winter, hospitals across the country have reported huge numbers of patients with respiratory symptoms, and some were stressed by the number of cases. Luckily, nothing lasts forever and as flu declines, the burden is slowly lifting.

What’s Next

As the weather warms and more people develop immunity after being infected, forecasts from the CDC and various modeling teams indicate that flu will continue to fall. Over the next few months, both the flu and RSV should fall to negligible levels, as they have each year going back as far as data is available, before surging again next fall and winter. However, given the extremely high level of flu activity, it may be over a month before hospitalizations and overall rates of illness can be considered “low.”

COVID is also decreasing, though it’s unlikely to fall as quickly as the other two viruses. There is also a likelihood of a large wave in the warmer months, be it in the spring, summer, or early fall. The exact timing and size of such a wave will largely be dependent on whether new variants of the virus emerge, which is notoriously difficult to predict. Will COVID continue to evolve at relatively slow rates as it has in the past few months, generating fewer cases than in past years, or is this winter a mere prelude to another active year? If variants with a strong escape from existing immunity emerge as they have in the past, another big wave in the middle of the year could be right around the corner.

Overall, it remains hard to predict exactly the future of respiratory viruses. The obvious contrast between this winter’s flu and COVID wave proves that the landscape for respiratory viruses continues to change. This is less dramatic with RSV, which remains a smaller threat outside of younger age groups, without drastic changes in its overall impact. However, RSV activity does seem to be shifting to later in the winter, reverting to the pre-COVID norm.

COVID, by far the dominant driver of hospitalizations each winter since it appeared in 2020, is still behaving more dynamically. It surges in the summer when similar viruses lay low, and the size and timing of its waves still vary considerably. Fortunately, its overall impact appears to be stabilizing at lower levels, which makes sense considering it’s far newer than RSV or flu. The flu remains confined to colder months and, like RSV, is reverting to the pre-COVID pattern of late winter surges, but the overall peak clearly varies widely from year to year.

Comments